From Barcelona to the world - How a student occupation changed university policy

In November, Elena, Lorenzo, Felipe and their fellow students occupied the University of Barcelona to fight for stronger action against climate change. Talking to them, TEMA author Daniel Harper reveals how their actions signal what could be possible for climate activism in Barcelona - and beyond.

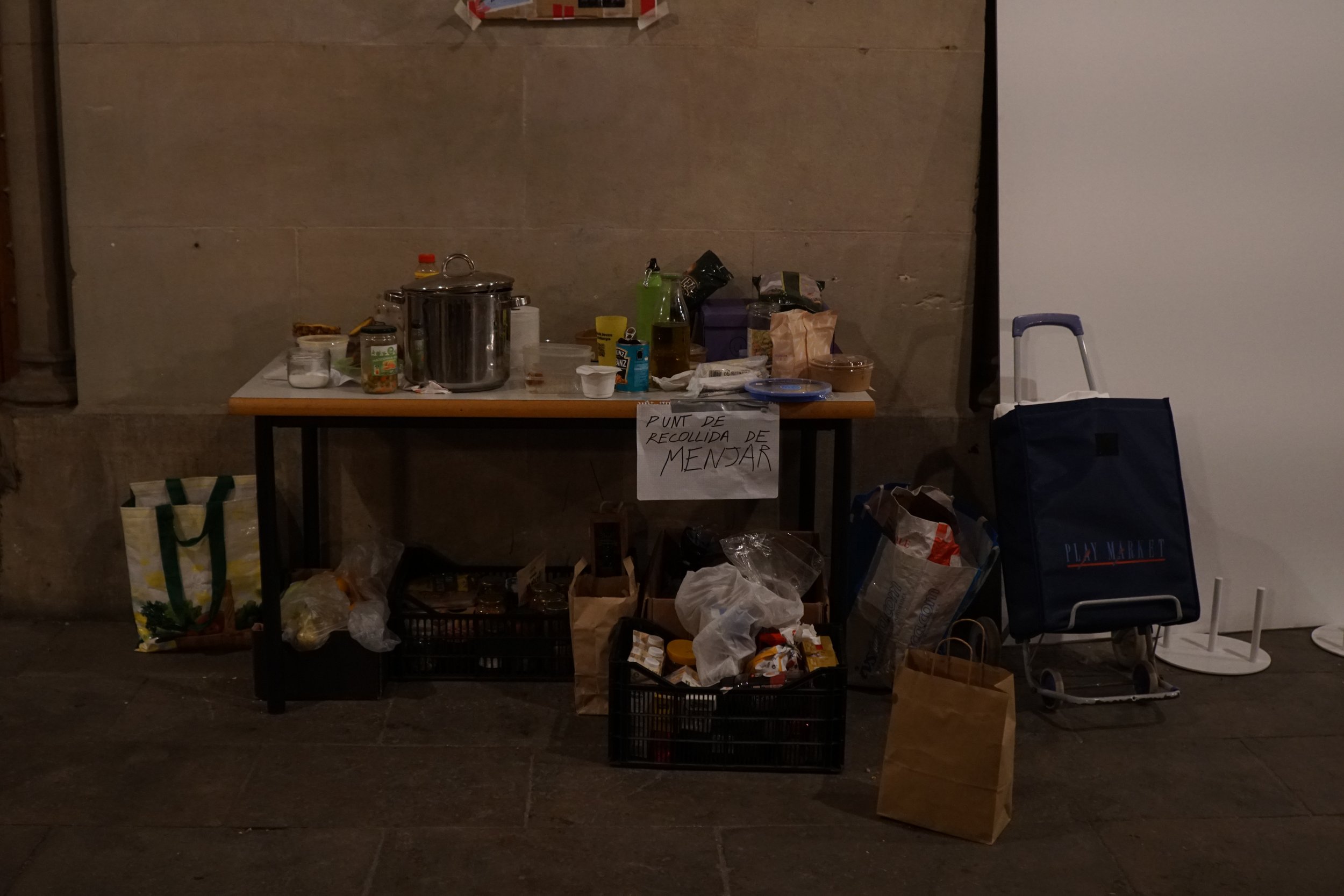

It begins to rain in the lush green garden at the University of Barcelona’s main building, where I wait to meet Elena Isidro Higueras, a master’s student of ecology at the university and core member of the activist group End Fossil Barcelona (EFB). It’s here, between the palm trees and the pillars, that Elena and other members of EFB slept for a week in an effort that their demands would be heard and enacted by the university.

Elena Isidro Higueras © Daniel Harper

Elena plays with the rings around her finger as she describes the events of last November, “There were lots of banners and good people. I have good memories about the occupation”, she smiles as I can see the memory pass in front of her. “If I spend my life fighting - at least my conscience is clear.”

The main demands of Elena and EFB were simple:

A compulsory course for all students on the social and ecological impact of climate change.

For the university to cut ties with fossil fuel companies, such as the energy company Repsol.

To stop dealing with banks that invest in fossil fuels, such as the Spanish bank Santander.

© Daniel Harper

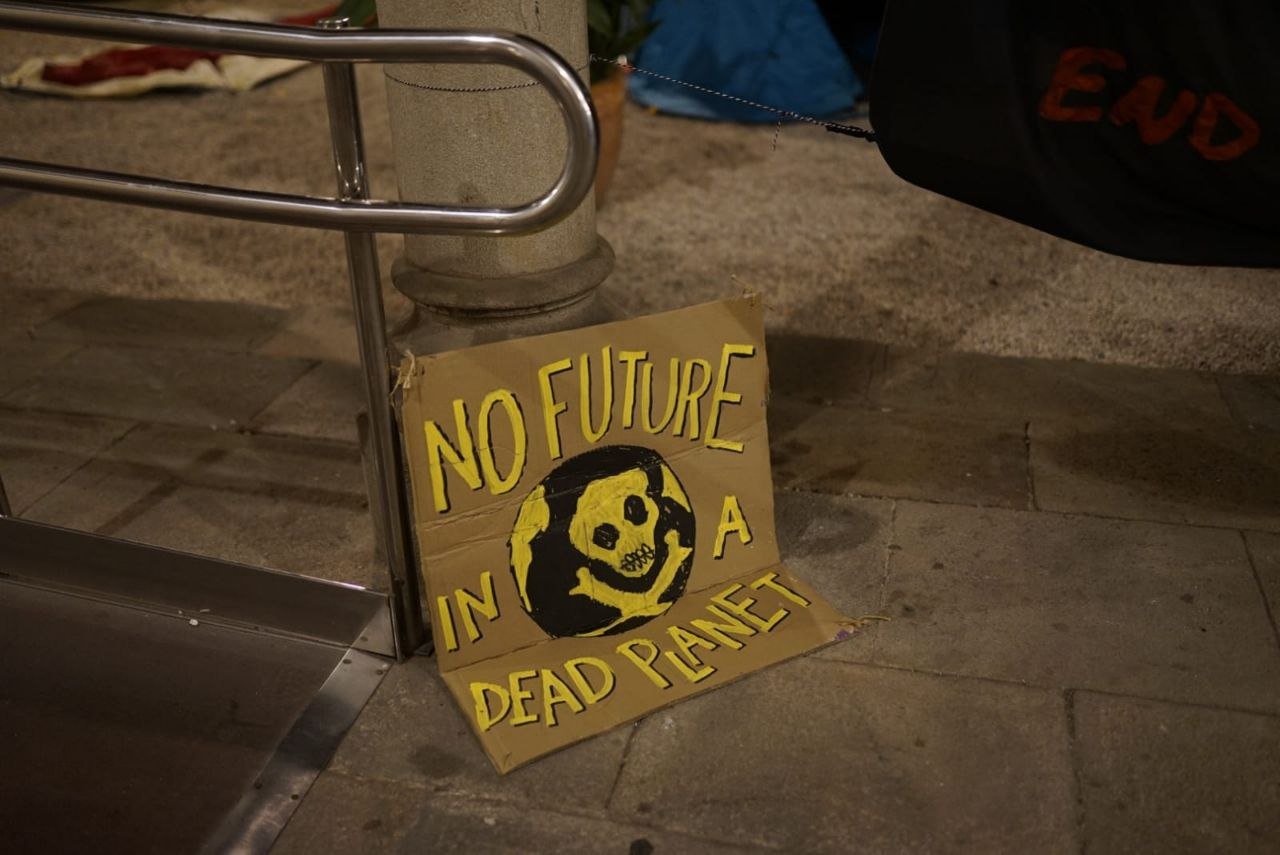

© Daniel Harper

The negotiations

Skimming through my prepared questions, I go off script and start simply with: How did it all go? Elena has moved from her rings to her satchel, twiddling her thumbs through the strap of her bag where one pin has ‘End Fossil’ written on it. “At the beginning, we prepared to stay for three days. We entered on Wednesday and by the time Friday came the negotiations were still going on and we thought we had to spend the weekend locked up.” I begin to get comfy, sitting by the pink petalled flowers of the garden, as Elena begins to tell me how EFB managed to get two out of three of their demands.

On the second morning of the occupation, a letter came from the university with a first attempt at negotiating. PhD student Lorenzo Velotti, one of the main negotiators for EFB, provided the context of the university's first letter to me over the phone. “The document they sent us was a lot of blah blah blah, in the sense that there was a lot of stuff saying the university is committed to climate justice, but there was no reference to our demands”. An assembly of the occupiers followed to discuss their next action. Some feared that declining the universities offer would result in reprisals to the students, but after talks it was decided the letter was redrafted and sent back, reinforcing the three demands.

A back-and-forth tennis match ensued between the university and the activists, both knowing the other could not go on indefinitely. “From then on, every day we had a new version of the document” Lorenzo explained, “they [the university] would send the proposal back to us where our demands were completely watered down, and so we would send it back reinforcing them and so it went on like that until the very last moment.” Unfortunately, there was no reply from the university negotiators when I tried to contact them for a comment on the occupation and negotiation process.

In the end, the document would be swapped a total of six times, with the activists pursuing the tactic of reinforcing its demands, waiting for a response, and reinforcing again until someone gave in. After a week it was over.

Through persistence and a clear aim of their demands, the occupiers were able to hold out in the garden, convening, discussing, and drafting their responses carefully. Going in, they had little idea it would take this long, but they were sure of the common goal: the university must commit to anti-fossil and pro-climate policy.

A story of success

After negotiations were settled a compulsory climate course was agreed upon. From 2024 the University of Barcelona will administer a course to all its 14,000 students and become one of the first educational institutions to make a compulsory class on the physical and social effects of the climate crisis.

EFB specified how the course should be operated, with names of renowned professors to work on the creation of the course that were trusted in their fields and who knew the scale of the climate crisis. It was stipulated that 60% of the course commission was to be made up of the names proposed by the students. This gave negotiating power to EFB, who are mostly made up of students, as they have direct access to the staff creating the course.

“It’s a challenge”, said Associate Professor Jofre Carnicer Cols, one of the names on the students' approved list, when asked about the difficulty of creating the course, “We are trying just to focus on the most fundamental issues and to provide a comprehensive and multifaceted course. We are doing open sessions composed of social and climate scientists, and specialists in human rights and trying to somehow define which are the key elements. This would include not only the climate but global inequality and global injustices.”

It wasn’t only the creation of the climate course but the severing of ties of fossil fuel giant Repsol with the university that cemented the occupation's victory. In December a cátedra, or professorship, funded by Repsol, was to be renewed with the university. When EFB heard who would fill the position, the group wrote to convince them not to take the role. It was rumoured that due to this social pressure, the cátedra remained unfilled, leading to Repsol’s ties to the university through the professorship being severed. When Lorenzo talks about the ripples that the occupations' successes have had, I can hear the pride in his voice: “It’s a demand that we didn’t get in the agreement, but we got in the end.”

Impacts beyond the University of Barcelona

Over another crackly phone call Felipe Martinez, student occupier and EFB member, tells me that “the demonstration has set a precedent for other countries”. This event has indeed inspired movements to spring up across the globe, but in Europe especially.

In January, it was announced that the Paris Institute of Political Studies was launching a compulsory course on ecological culture. Many university students and professors from across the EU, North America, and Australia have been contacting EFB to hear how they were able to achieve their demands.

It seems blunt, but I ask Lorenzo why it all was such a success. “Our struggle and results became inspirational for thousands of students and many universities around the world”, he begins to tell me, “It sets a precedent that cannot be ignored. Social movements need victories in order to galvanise their struggles, this was a relatively big one, at least big enough to revitalise parts of the climate justice movement. It sparked interest also because of the novelty of the tactics, which differed from previous ones by the climate movement”

The attention brought by the media made the results known throughout the climate movement, as well as the academic scene. “Such a compulsory subject has never been offered before at any other university.” Elena explains to me, “For this reason, we got the attention of the international media”. From the publicity, the message was sent beyond the regional bubble and into the minds of people everywhere.

Moving forward

The rain has stopped in the garden as Elena and I walk between the Catalan styling of the brown gothic architecture. The success of the occupation has encouraged the activists as they step into the future, invigorated from their victory. “The most important thing for us was to have created links, both between us, which helps us to continue fighting, and with other groups and people who knew us,” Elena tells me. “For this reason, we continue to be active with a lot of work on our hands and new occupations ahead. We've learned a lot about how things work and tactics to engage the public and official institutes, it's been a learning process for me and my group. Now we will scale up and demand things from the government.”

May 2nd will see another call by End Fossil for students to occupy universities and schools, with further plans by the Barcelona branch to organise further demonstrations.

The future is uncertain, both for the planet and the activists in Barcelona, but one victory has brought a new level of confidence to the climate movement in the city; whether this is enough however is still unclear. Nicole Claesson, a local activist from Futuro Vegetal, reminds me, “It’s amazing it came true, but I don’t think it’s a big step either, it’s necessary to inform the kids about their future. It’s something good but we don’t have that much time. We need bigger, more drastic changes.”

It’s spring and although Catalonia is suffering its worst drought in decades, it's difficult not to notice the deep purple petals of the flowers that are blooming beautifully in the garden. All over the local news water reserves are reaching almost critical lows of 27%, reminding us that the impact of climate change is already affecting this part of Europe, but in this garden, there has bloomed, possibly, hope that change can be made to better the future.

Pink petalled flowers in the garden of the University of Barcelona © Daniel Harper