To each their own roof

Homelessness numbers in Europe are rising. Amidst a host of different crises, the housing first* concept has been hailed by many as the saving grace. But can it change a basic conception deeply woven into the very fabric of our society?

*Housing first: Housing first is a concept that advocates for permanent housing to homeless people without any formal requirements. This perspective gives the right to housing a priority, other supportive measures only come in effect after one is decently accommodated. The concept became popular in the 1990s, and in the following years the US and various other countries employed it as a government policy.

I am five minutes early, my train is 20 minutes late. Looking around, I see a man walking across the platform, asking for money to pay for a bed in the night shelter. Some people just ignore him, and he retreats away from them. Some give a little, most say no. I say, “sorry, I don’t have cash with me”, which isn’t true.

This is a common occurrence in Europe’s capitals which have seen a steadily increasing number of homeless people. The pandemic, a lack of social or public housing and rising poverty levels have 700,000 people sleeping rough on any given night in the European Union, marking an increase of 70 per cent in the past ten years. Still, these are only the ‘hard cases’, of people who experience chronic homelessness for long periods of time, sometimes paired with psychiatric illnesses or substance addiction. In the bigger picture, they are the rarest cases. Temporary homelessness is much more common, most of those who sleep in shelters are gone the very next day.

How to swim without water?

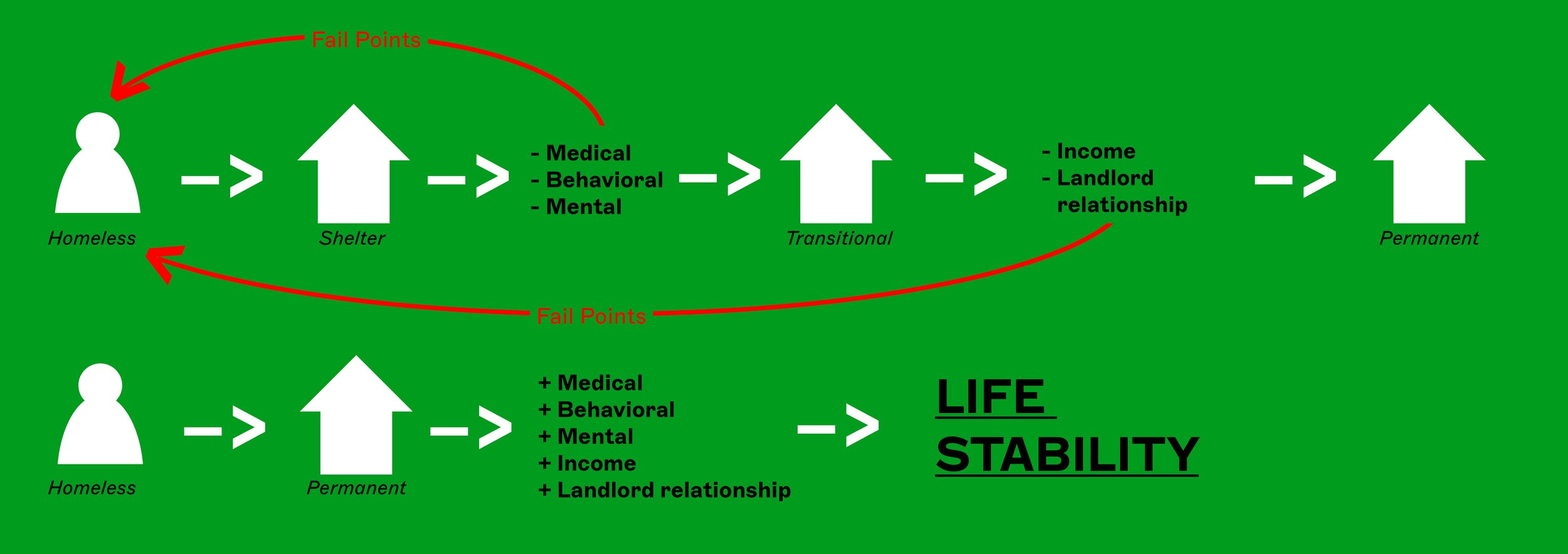

Rising numbers are not the only issue, says Volker Busch-Geertsema, who has researched homelessness for the past 30 years: “I think we have accepted that there is just always going to be people sleeping on the street”. This notion has very much manifested in the way authorities have traditionally treated the problem, as many countries organise their basic assistance systems in a ‘staircase model’*. People who are suffering from chronic homelessness herein have to show they are ‘housing ready’, before they are deemed fit to live in their own dwelling. Sometimes, this means being bound to conditions like getting psychological treatment or staying clean, which can be additionally challenging when lacking a safe personal space. “How are you supposed to show you’re ready to live in an apartment without an apartment? It’s like learning to swim without water”, says Busch-Geertsema.

*Staircase model: The staircase model a description of the basic assistance system used by most welfare states. It means that homeless people are required to stick to certain rules, for example to abstain from drugs and alcohol, before they are eligible for social housing.

An approach that promises to challenge the basic understanding of homelessness, was developed by the U.S.-American psychologist Sam Tsemberis in the 1990s. Working at Bellevue hospital in New York City, he would see the people he was treating at work again on the street on his way back home. Seeing that the staircase model didn’t work for certain hard cases who came back to the streets over and over, he created the ‘Pathways to Housing’ foundation, which aimed at turning the staircase model on its head. His housing first method put people in apartments and then let them choose if they wanted support, thus reversing the traditional succession of steps. The evaluation of the first model project in New York City attested that 88 per cent of people who were given their own apartment right away, remained housed after three years.

The steps of housing readiness and advantages housing first brings with it.

Housing first: From the US to the EU

Housing first caught on quickly in the U.S. but took some time to gain traction in Europe. Denmark launched the first stage of a successful program from 2009 to 2013 and Finland has been widely celebrated for devising a radical national housing first strategy as early as 2008. Taking the original idea as a basis, it cleverly fitted Tsemberis’ model to domestic needs. Shelters were turned into separate residential units and new apartments were bought from the private market to make up for a lack of social housing. Today, Finland is the only country in the EU where homelessness is decreasing.

A slow burn

Not everyone has been so swift to act. Of course, as a consequence of the privatisation of housing markets, many have to deal with a catastrophic shortage of social housing. But this doesn’t serve as a thorough explanation. The fact that people who have fallen through the cracks of the social safety nets and have a hard time finding an apartment on their own is accompanied by the logic of homeless people having to earn their ‘right’ to housing. Many traditional assistance providers do have their own residential housing units, but they are usually not in the business of constantly acquiring new apartments. “They receive their legitimacy by getting people prepared to be housed, not by permanently housing them”, says Busch-Geertsema.

When evaluations of several European pilot projects in the early 2010s once again showed high retention rates, housing first was thought to proliferate quickly. In some ways it did, with experimental projects sprouting all over the EU. But the division of funding between traditional systems and housing first has proved to be a difficult obstacle. Juha Kahila, who is part of the Y-Foundation which developed the Finnish strategy back in 2008 and works with the European Housing First Hub, says the time has come to plan more comprehensively: “I think we need to put more pressure on local authorities and decision-makers to change their strategy. The problem is, when the projects end, where do the tenants go?”

Deadline: 2030

One way to go forward could be the combination of both models within a productive division of labour. “I think, the field of work for the traditional assistance providers should move more in the direction of prevention. It doesn’t make sense to let people who suffer from psychiatric diseases become homeless and then focus all efforts on getting them back into housing”, says Busch-Geertsema.

But no matter how homelessness is being tackled, there is bound to be a paradigm shift in its societal understanding.

At least the EU seems to have heard the call. In June 2021, its members pledged to work towards ending homelessness altogether by 2030. Of course, words have to be followed by actions, but working to change the fact that homelessness is an issue here to stay, must be seen as a step in the right direction.

Bibliography

Journal Articles / Books

Fondation Pierre Abbé, FEANTSA (2021) Sixth Overview of Housing Exclusion in Europe. Brussels: FEANTSA.

Pleace, N. & Bretherton, J. (2013) The Case for Housing First in the European Union: A Critical Evaluation of Concerns about Effectiveness. European Journal of Homelessness, 7(2), 21-41.

Pleace, N. (2016) Housing First Guide Europe. Brussels: FEANTSA.

Ridgway, P., & Zipple, A. M. (1990). The paradigm shift in residential services: from the linear continuum to supported housing approaches. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 13(4), 11.

Tsemberis, S. (1999) From Streets to Homes: An Innovative Approach to Supported Housing for Homeless Adults with Psychiatric Disabilities. Journal of Community Psychology, 27(2), 225-241.

Web

Further Reading

Gladwell, M. (2006) Million-Dollar Murray. Homelessness and the power-law paradox. The New Yorker, Issue No. 5, 96-107.