Self-images of aging: presence and desire in the work of women artists

“I wanted to see what would happen. I have to take a chance. I don’t want to get stuck in the pathology of aging; I want to do the reverse. I want to normalize age. How does one do that and still be seductive? That is what I’m thinking about.”

Of all the privileges one may be born with, youth is the one that everyone is granted, and that all lose (continuously) throughout their lifetimes who do not die young. For women, the creeping loss is seemingly more palpable and aging a constant issue as the impossible imperative is to postpone visible aging. Within my peer group, I forget my age - until I encounter people half my age, and the age difference becomes apparent. I take pleasure in their youth and, at the same time, am happy to have outgrown my own self at their age. Even though I come from a different generation, I still feel close to some of them, because common interests often bond more than the same ages. But I also look in the other direction: what role models exist for my future as an older woman? Particularly being an artist who is no longer quite young, but middle-aged, I look for examples and images of older women* within the arts that are exciting and also show them as desirable and desiring subjects.

This motif is repeated in contemporary culture as well. One example is the juxtaposition of Kylie Minogue in an advertising clip for the underwear label Agent Provocateur with an older actress who, due to the set design and her over-the-top styling, comes across as a brothel madam. The latter partakes in the “experiment” to prove that the aforementioned underwear brand is “the most erotic”. For this purpose, Minogue rides on a mechanical rodeo bull. The short clip ends with the witch-like laughter of the old woman.

When we talk about the depiction of women* in visual art, it is usually a white woman; with few exceptions, she is beautiful, able-bodied, and most often young. When I go over the history of art in my mind, I find few prominent depictions of old women. Exceptions that come to mind are depictions of Saint Anne, Dürer's mother (and other mothers and grandmothers), Rodin's sculpture of an old woman, and jolly to feisty old women in genre paintings of the 17th and 18th centuries. The old woman in the role of a matchmaker of a couple is a popular subject especially during the Baroque period, for example in the work of Jan Vermeer or Gerrit van Honthorst. The old woman is used in a moralising way: Read image-immanently, she admonishes the young woman who is the object of desire that she, too, will one day lose her beauty; but she also serves as a reminder to the suitor, for she is in attendance to receive her share in the prostitution, thus making it clear that the access to the young woman is bought. As a grotesque figure, she also warns the viewer against the arrogance of youth – and by extension: beauty and lust – and simultaneously, in juxtaposition with the young woman, she reinforces the latter's attractiveness. The old woman is portrayed as abject.

The Old Courtesan (La Belle qui fut heaulmière), Sculpture-Bronze, Auguste Rodin

The procuress, 1625, Gerrit van Honthorst

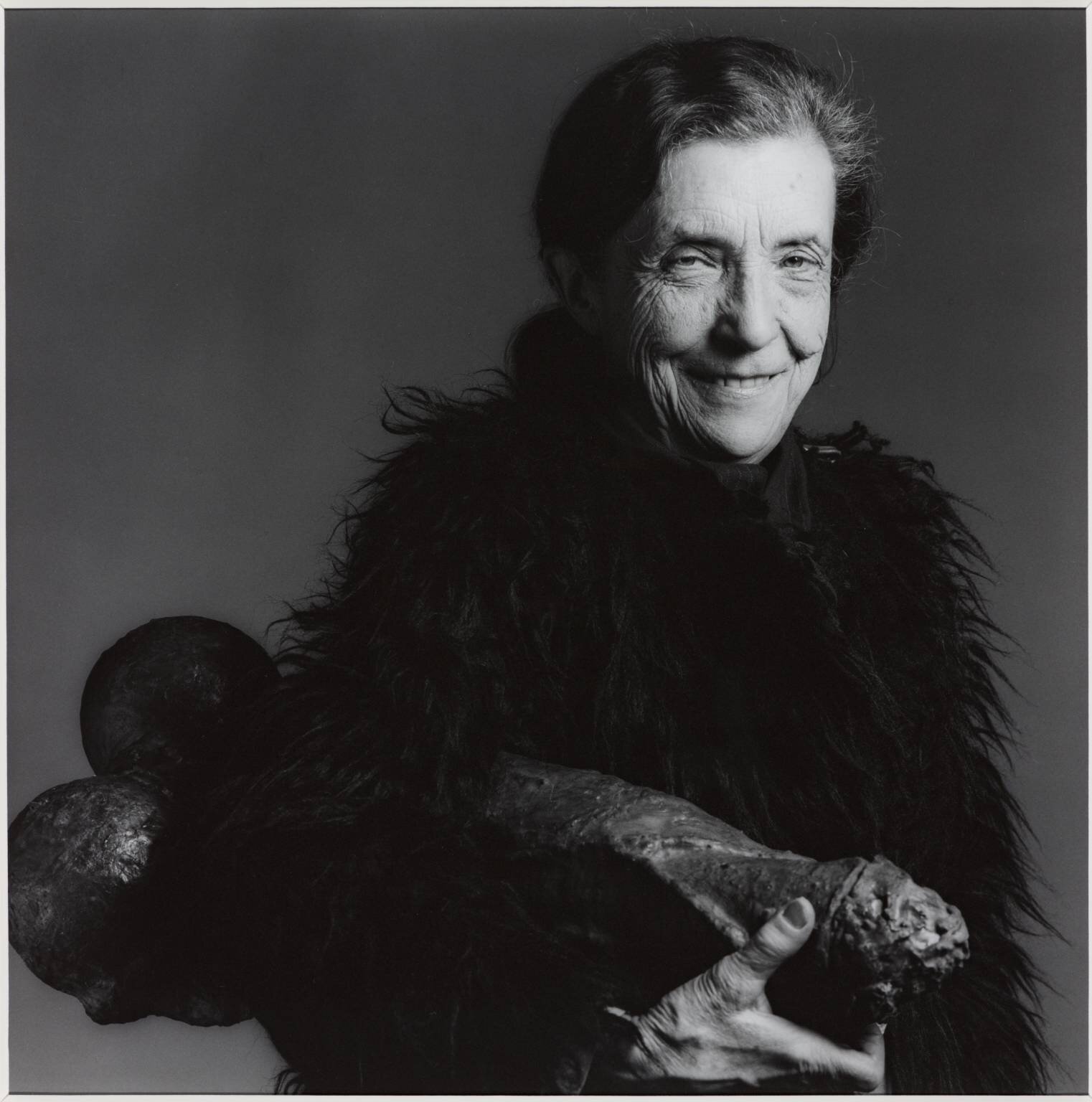

In 1982, Robert Mapplethorpe had been commissioned to photograph artist Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) for her retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. Bourgeois had come to the appointment prepared: she brought her sculpture Fillette, 1968, as a prop. In the well-known portrait, Bourgeois wears the phallic work tucked under her arm. The pose and her gaze directed straight at the camera emphasize that she was not simply the object of the photograph, but acting on her authority. For the exhibition catalog, the motif was cropped at her shoulder. Bourgeois commented on this as follows: “The glint in the eye refers to the thing I’m carrying. But they cut it. They cut it because the museum was so prudish.” (Robert Mapplethorpe: Louise Bourgeois, on the website of Tate galleries.) The museum's curatorial team or its PR department shied away from showcasing the artist, whom they honored in her old age with the retrospective, with an overtly sexual artwork. One could speculate that this censorship of the image stemmed from the prudishness of depicting a phallic sculpture, or that the explicit physicality of the object was incompatible (in terms of publicity) with the image of the old lady. What is certain is that a decision was made here which curtailed Bourgeois in her artistic self-expression.

© Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe: Louise Bourgeois, 1982. In: Wye, Deborah. Louise Bourgeois (Ausstellungskatalog), S.4. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1982.

With this article, I do not intend to suggest that depictions of sexuality are necessary for (older) women as part of their self-empowerment. However, I believe that societal and cultural censorship of the sexuality of older women is discriminatory and affects the female self-image. The absence of depictions of later life sexuality of particularly women within media and visual arts is notable. While older men are still granted sex appeal, especially in connection with younger partners that seem to support this, representations of older women with younger male partners are rare.

To illustrate this point and demonstrate how the narratives of age and gender are reflected in the work of artists, I shall juxtapose works by Alice Neel and Lucian Freud, two painters whose practice is marked by a devotion to portraiture, particularly nude portraiture, and is comparable on several levels.

Alice Neel portrait in her studio by ©Lynn Gilbert 1976, New York

The work of the painter Alice Neel (1900-1984) is characterised by a clear perception of the people she made her pictorial subjects. In the late 1920s, she mostly made autobiographical paintings from imagination. Then, Neel increasingly began to depict her surroundings and the people in them, until, during the second half of her life, the style of portraiture for which she became known had matured. Just like Freud, Neel preferred her family members, lovers, friends as models. Many of these portraits are nudes: women, men, even children. Their bodies are defined by broad strokes of colour that become increasingly colourful over the decades, always contoured by expressive lines, and devoid of idealising tropes. Helen Molesworth describes the paradox of Neel's paintings as charged with “an undeniable charge which can only sometimes be described as erotic,” even though the works themselves seem to deny the erotic. Further, Molesworth speaks of the nudity in Neel's nudes, referring to their immediacy. Looking at her paintings, one can imagine that Neel is piercingly observing her models, as they definitely look back from the canvases. The model is at eye level with the perspective of the viewer. Neel probes courageously, without ingratiation, and full of truthfulness to her sitters. Her paintings, in which she depicts (heterosexual) relationships or where her desire seems perceptible, are also characterized by freedom from the expectations of gender roles. Pregnant Julie and Algis, 1967, is a double portrait of a pregnant woman who is naked and a clothed man who is lying behind her. The polarity between the clothed and the naked person, however, does not seem to express a power disparity. The nakedness of the pregnant woman appears to be challenging us, as though the model, or Neel, is refusing to conform to romantic ideals of motherhood. We can find a similar expression in her numerous paintings of pregnant women, alongside looks of insecurity – also an emotion omitted from depictions of pregnant women.

The people in her paintings do not need others to define them. Neel shows their sexuality and physicality as an aspect of being human, regardless of whether the person is a child or an adult, of gender and age. Her work depicts a wide variety of states and stages of being, such as her paintings that capture postpartum, or the portrait of Andy Warhol, the scars visible on his ribcage from the 1968 assassination attempt on his life. Neel describes a range of female lived experience: both how women experience themselves outside of a male frame of reference and their response to it. Denise Bauer conveys this sensibility as follows: “It is Neel's skill at capturing and deconstructing this complex blend of what women are ‘supposed to’ experience and how they may actually experience the male gaze that expertly cuts to the reality of so many women's experiences of themselves and their bodies.”

There are several filmed interviews with Neel after she gained recognition at over seventy through a retrospective at the Whitney Museum; people suddenly wanted to hear from the old artist whose work had been legitimised by an institution. In them, she emerges as a bright and feisty woman who rejoices in her success – but who had also straightforwardly created a major body of work during fifty years without the visibility of a wider public. At the age of eighty, Neel portrays herself naked, with a brush and painting rag in her hand, sitting on an armchair, which also appears in other paintings. Neel shows herself alone, autonomous, self-confident. Her pose in a three-quarter profile differs from the mostly frontal perspective on her models. This can be explained by the execution of the work: Her gaze had to wander back and forth between mirror and canvas; to move as little as possible, she mainly turns her head. She places herself in the line of tradition of artists who show themselves in the execution of their work, thereby pictorially underscoring their self-expression and their agency. The composition is reminiscent of Lucian Freud's nude self-portrait Painter Working, Reflection, 1993. Both painters expose themselves in the same way as they present their models; they show themselves stripped bare in their studios while painting. Freud wears only his working boots without laces, holding a palette in one hand and a painting spatula in the other. He handles his image as bluntly as one would expect from his work, presenting himself with his body erect yet marked by age.

Lucian Freud (1922-2011) created numerous self-portraits throughout his life. In addition to Painter Working, Reflection, a second painting shows him at an advanced age engaged in artistic activity, which I will use to draw a comparison with Alice Neel's self-portrait. The work The Painter Surprised by a Naked Admirer, 2004-2005, is also a statement on his work. In this painting, however, Freud pictured himself clothed, with a young nude female model at his feet, and painting the image we see, making it a meta-painting within his oeuvre –though arguably one of his least accomplished works. The juxtapositions of clothed/nude, upright/crouching, passively begging/actively painting reproduces a gender dichotomy depicted countless times, making the woman the object of the gaze. Interestingly, the sexualisation of the nude does not occur in his other (nude) portraits, which are executed with a ruthless but devoted realism. It is well-known that Freud's female models were often lovers or became so in the course of the painting process, moreover, some of them are mothers of his children. And yet he paints men, such as his assistant David Dawson or Leigh Bowery, with the same intimate intensity. In the second half of his life, Freud's work gains artistic expression and acclaim. It is therefore surprising that Freud, who rejected psychological or symbolist interpretations of his work, staged such a painting at the age of eighty-two, and insisted on displaying it prominently in the National Portrait Gallery. The press called the title “humorous.” The Guardian quotes a writer and friend of Freud's who describes the young woman in the painting as “a muse or a nuisance, maybe both,” and her pose, in which she seems to cling beggingly to Freud's leg, as “very touching […] you get a very strong sense of a relationship.” Further, the interpretation of the crouching model is a personification of Painting itself, in admiration for the old master — thus, in keeping with art historical tradition, the woman is stripped of her identity and functions as an allegory. In this painting, Freud perpetuates his image as an attractive artist for whom everyone, but especially every woman, wants to be a model. The gesture of imaging himself with a model at his feet is the power gesture of a heterosexual male artist, and thus hardly conceivable painted by a female artist.

Far beyond the staging of the self by female artists, the use of one's own body and one's image is an effective device for constituting one's agency. This is especially significant to correct the prerogative of interpretation of images, about who is represented and in which way. For feminist artists, this is a deliberate and effective strategy.

Suzy Lake (*1947) has been using her own likeness since the early 1970s to engage performatively and photographically with representations of women and femininity as masquerade. Unlike Cindy Sherman, whose work has been influenced by an early encounter with Lake, she uses self-dramatisation not to depict various female characters, but to show how women, in particular, are confronted with societal expectations about the way they present themselves. Sara Angel quotes Lake: “I knew what I should look like […] I was told that all my life.” What began as an exploration of magazine images, cultural imprints, and fashion notions, led to examining the paired stereotypes about age in the Western world – a man matures as he ages; a woman withers – as a political act.

In media images that, especially in women, favour youthful beauty, women increasingly fall through the cracks. As if to counteract the gradual disappearance of women as protagonists as they grow older, Lake created works that make her presence the subject matter. In the piece Extended Breathing Under Porch Light, 2009–2010, Lake captures herself with long exposure within a domestic garden. She must stand still to keep her image from blurring, to keep from disappearing. “[She] is insisting on a presence inside the frame […] I think it’s about a much broader question of how women insert themselves inside of a social and political space”. The invisibility as a woman of a certain age is one possible reading, also the ambivalence between being a white woman, possibly a housewife, who lives in a fenced-in single-family home with a garden, seemingly privileged but primarily socially relevant as a consumer. Another declination of the theme is to be seen in the series Reduced Performing, 2008-09, for which Lake lay on a flatbed scanner in various outfits and performed minimal actions: breathing, blinking and crying. Her clothing is characterised by unpretentious normalcy; it could be Lake's everyday attire. Where her body moves during the scanning process, blurring or glitches occur.

The artwork Performing Haute Couture, 2014, is the counterpart in terms of its content. Lake shows herself well-illuminated in a proud pose wearing a Commes des Garçons two-piece. Here she slips into a role attributed to older successful women: That of the grande dame. The styling suggests the likes of performance artist Marina Abramovic or Anna Wintour, editor-in-chief of U.S. Vogue, of women from the intersection of high society and culture. According to Georgiana Uhlyarik, the image created is a statement to illustrate and embody “commerce, fashion, desire, ambition, influence.” (Uhlyarik, Introducing Suzy Lake, 173.) Here an ambivalence is tangible: on the one hand, Lake manifests herself as successful, self-empowered, and self-determined – she presents Suzy Lake, her own creation –, while at the same time, she makes the construction of this identity already evident in the title of the work, as in all of her work.

At the age of approximately forty, the painter Joan Semmel (born 1932) began to incorporate images of her body into her paintings. Her early work was marked by the strong aura of the so-called New York School. After living in Spain for several years, she returned to New York in 1970 and found herself confronted with sexualised media images in the cityscape. It was under this influence that Semmel began to paint her first sexual pictures. From quick expressive drawings based on imagination and models, gestural paintings emerged. To depict a more accurate vision, she eventually worked from self-made photo references of intimate couples but broke the realism in her figures through their colouring.

“I was never figural. What I was looking for were images that were iconic. I was looking for ways of making images that women would see as sexual for them, and so I wanted those images to register, and that is part of why I left the abstraction behind — because the abstract images are more diffuse.”

In Semmel's work, sexuality is not treated critically or ironically, as, for example, the sculptor Lynda Benglis did in her ad in Artforum (1974), when she posed with an oversized dildo, or esoterically, as some of Judy Chicago's pictorial works may appear; rather, it is an earnest exploration of the subject. Tied to this is the portrayal of equality between the heterosexual couples she depicts, which contrasted with the representation of sexuality seen during the pornographic wave of the 1970s. Joan Semmel is close to her model – whether it is herself or another person – and thus conveys veracity that is unadorned but sensual.

“Pornography is fashionable now; it is considered fine, just another entertainment. But the attitudes that are expressed in most pornography are abhorrent. My sexual paintings might be very disturbing to these same people who watch pornography because the dehumanizing aspect is no longer there. So it makes them nervous.”

The direction of the gaze in her paintings is remarkable. Although Semmel often crops the bodies so that the heads are outside the frame, which can be read as dehumanising or objectifying, the extreme perspective used in many of her works causes the viewer to look at these fragmented bodies as if they were looking down at their own physical selves.

As a logical consequence, Semmel inserted herself – alone or with a partner – into her paintings. The painting Intimacy/Autonomy, 1974, shows Semmel and a man from the collarbones down; they lie close together with their legs drawn up but do not touch in the picture field. In her self-portraits, Semmel initially turns her point of view through subjective cropping into the viewer's first-person perspective, as in On the Grass, 1978. Later, she accomplishes this by incorporating mirror images into the compositions, as in Body and Sole, 2004. Both paintings show similar parts of her body: bent legs, the abdomen folding as a result of her postures, breasts. In the second painting, however, one of her feet is doubled, as much of the painting is taken up by a reflection. From it, Semmel – with the camera pointed at herself – looks back at us as onlookers. Semmel called this reversal “a destabilisation of the viewer and the viewed.” (Silas, “On Sexual Paintings and Shifting Images.”)

Joan Semmel 2018 at ©The Jewish Museum, photo by Sara Wasserman

In the 1980s and '90s, Semmel explored both the social and media gaze upon women's bodies in different series of works, as well as the judgmental male gaze that women have internalised. Her motifs include self-portraits in gym locker rooms, mannequins, or bodies on the beach. In the last twenty years, she has turned back to nude self-portraits that show her alone, but where she often multiplies herself. Painted in translucent layers, some works resemble Eadweard Muybridge's movement studies (e.g., Triple Play, 2011). Others bear a ghostly quality (Disappearing, 2006) that seems to allude to the fragility of life which becomes noticeably more prevalent as we age. Significantly, these artworks show her as a whole figure, as if she wanted to contemplate these thoughts embodied in herself, and needed a certain distance to do so. In her recent works, Semmel, now well into her eighties, has returned to depicting the first-person perspective on her own body. The fact that she is still a beautiful woman does not diminish the importance of seeing large-format nudes of an old woman who shows herself confidently in her physicality without needing validation, without needing to please.

I began this mental excursion into the works and self-portrayals of older women artists searching for alternative images of womanhood. When we turn our gaze from taut young bodies to a subjectivity, is it possible to find an expanded portrayal of corporeality? Here, both presence and sexuality are subjects on equal footing, and they are correlated. Poet and activist Audre Lorde wished for a celebration of the erotic in every situation. She understood the erotic not only sexually, but as a life force: “In touch with the erotic, I become less willing to accept powerlessness, or those other supplied states of being which are not native to me, such as resignation, despair, self-effacement, depression, self-denial.” Lorde writes how, as a Black lesbian, she has directly experienced this erotic charge, but women operating within an “european-american male tradition” cannot readily experience it. For Lorde, the contemplation of the erotic as a profoundly creative source, is, in the face of a racist, patriarchal, and anti-erotic society, a feminine and self-empowering act.

The invisibility of older women and their sexuality is rooted in the cultural association of beauty with fertility. On the one hand, sexuality is culturally anchored in the female body, but this seems to hold only as long as the woman is young, capable of childbearing, or has been able to maintain her physical youthfulness. Although older women are "granted" sexuality, its representation is rare – this includes sexual self-representation in the work of older women artists. If we assume bodies as discursive entities rather than essential and biological, then desire can be thought to be textually and performatively inscribed into corporeality. Neel, Lake, and Semmel defy the expectation that women* retreat gracefully past a certain age. By using their bodies, that is, their likeness in their art, they manifest their agency.

±

Selbstbilder des Alterns: Präsenz und Begehren im Werk von Künstlerinnen*

“I wanted to see what would happen. I have to take a chance. I don’t want to get stuck in the pathology of aging; I want to do the reverse. I want to normalize age. How does one do that and still be seductive? That is what I’m thinking about.”

Von all den Privilegien, mit denen man geboren werden kann, ist Jugend das eine, welches jedem Menschen zuteilwird, und alle zu Lebzeiten (kontinuierlich) verlieren, die nicht jung versterben. Für Frauen* ist der kriechende Verlust scheinbar spürbarer und Älterwerden immer ein Thema, weil der unmögliche Imperativ lautet, sichtbares Altern aufzuschieben. Innerhalb meiner Peer Group vergesse ich mein Alter – bis ich Menschen gegenüberstehe, die halb so alt sind wie ich, und die Altersdifferenz offensichtlich wird. Ich erfreue mich an deren Jugend und bin gleichzeitig froh darüber, über mein eigenes Ich in ihrem Alter hinausgewachsen zu sein. Auch wenn ich aus einer anderen Generation komme, fühle ich mich manchen von ihnen doch nahe, denn gemeinsame Interessen verbinden oft mehr als gleiche Jahrgänge. Aber ich schaue auch in die andere Richtung: Welche role models gibt es für meine Zukunft als ältere Frau? Insbesondere als Künstlerin, die nicht mehr wirklich jung ist, sondern mittleren Alters, suche ich auch in der Kunst nach Beispielen und Bildern von älteren Frauen*, die spannend sind, und sie auch als begehrenswerte und begehrende Subjekte zeigen.

Wenn wir über die Darstellung der Frau* in der Kunst sprechen, so ist diese meist eine Weiße Frau; mit wenigen Ausnahmen ist sie schön, able-bodied und fast immer jung. Wenn ich die Kunstgeschichte vor meinem inneren Auge Revue passieren lasse, dann sehe ich wenige prominente Abbildungen von alten Frauen. Als Ausnahmen fallen mir Darstellungen der Heiligen Anna, Dürers Mutter (und weiterer Mütter und Großmütter), Rodins Skulptur einer alten Frau und fröhliche bis feiste alte Frauen in Genregemälden des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts ein. Die alte Frau in der Rolle der Kupplerin eines Paares ist ein besonders beliebtes Sujet während der Barockzeit, z.B. bei Jan Vermeer oder Gerrit van Honthorst. Die alte Frau wird moralisierend eingesetzt: Bild-immanent gelesen, mahnt sie die junge Frau, die das Objekt der Begierde ist, dass auch sie eines Tages ihre Schönheit verlieren wird. Aber sie dient auch dem Freier als Mahnung, denn sie ist anwesend, um ihren Anteil an der Prostitution entgegenzunehmen, und verdeutlicht damit, dass der Zugang zu der jungen Frau erkauft ist. Auch die Betrachtenden warnt sie als groteske Figur vor dem Hochmut der Jugend – und in der Verlängerung: der Schönheit und der Lust – und gleichzeitig verstärkt sie, in der Gegenüberstellung mit der jungen Frau, deren Attraktivität. Die alte Frau wird als abjekt, sprich als verabscheuungswürdig, dargestellt.

1982 wurde Robert Mapplethorpe beauftragt, die Künstlerin Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) für ihre Retrospektive im Museum of Modern Art zu fotografieren. Bourgeois kam vorbereitet zu dem Termin: Sie brachte als Requisite ihre Skulptur Fillette, 1968, mit. Auf dem bekannten Porträt trägt Bourgeois die phallische Arbeit unter ihren Arm geklemmt. Die Pose und ihr direkt in die Kamera gerichteter Blick verdeutlichen, dass sie nicht einfach Objekt des Fotos ist, sondern selbstermächtigt agiert. Für den Katalog der Retrospektive wurde das Motiv an ihrer Schulter beschnitten. Dies kommentierte Bourgeois wie folgt: „The glint in the eye refers to the thing I’m carrying. But they cut it. They cut it because the museum was so prudish.“ (Robert Mapplethorpe: Louise Bourgeois, on the website of Tate galleries.) Das Kuratorium des Museums, oder dessen PR-Abteilung, scheute davor, die Künstlerin, die sie im Alter mit der Retrospektive ehrten, mit einer eindeutig sexuellen Arbeit zu zeigen. Man könnte spekulieren, dass diese Zensur des Bildes von der Prüderie herrührte, eine phallische Skulptur abzubilden, oder dass die explizite Körperlichkeit des Objektes (öffentlichkeitswirksam) unvereinbar mit dem Bild der alten Frau sei. Sicher ist, dass hier eine Entscheidung getroffen wurde, die Bourgeois in ihrer künstlerischen Selbstdarstellung beschnitt.

Ich möchte in diesem Artikel nicht behaupten, dass die Darstellung der eigenen Sexualität für ältere Frauen als Teil ihrer Selbstbehauptung notwendig sei, jedoch bin ich der Überzeugung, dass die gesellschaftliche und kulturelle Zensur eben jener Sexualität diskriminierend wirkt und das Selbstbild von Frauen* beeinflusst. Die Abwesenheit der Darstellungen von Sexualität im späteren Lebensalter, vor allem von Frauen, in Medien und Kunst ist bemerkenswert. Während älteren Männern immer noch Sex-Appeal zugestanden wird, vor allem in Verbindung mit jüngeren Partner*innen, die dies zu belegen scheinen, sind Repräsentationen von älteren Frauen* mit jüngeren Partner*innen sehr selten.

Zur Illustration dieses Sachverhaltes und wie sich die Narrative von Alter und Geschlecht im Werk von Künstler*innen wiederfinden, möchte ich beispielhaft Werke von Alice Neel und Lucian Freud gegenüberstellen, zwei Maler*innen, deren Praxis von der Hingabe an das Porträt, insbesondere das Aktporträt, gekennzeichnet und auf verschiedenen Ebenen vergleichbar ist.

Das Werk der Malerin Alice Neel (1900-1984) ist geprägt von einem klaren Blick auf die Menschen, die sie zu ihren Bildmotiven machte. Während sie in den späten 1920er Jahren, oftmals autobiografisch, nach ihrer Vorstellung malt, beginnt sie später zunehmend ihre Umgebung und die Menschen darin abzubilden, bis in ihrer zweiten Lebenshälfte der Stil der Porträtmalerei, für den sie bekannt wurde, reift. Genauso wie Freud bevorzugte Neel ihre Familienmitglieder, Geliebte, Freund*innen als Modelle. Viele der Porträts sind Akte; Frauen*, Männer*, auch Kinder. Ihre Körper sind durch großzügige Farbflächen definiert, die mit den Jahrzehnten zunehmend farbiger werden, stets mit expressiven Linien konturiert, und bar idealisierender Tropen. Helen Molesworth beschreibt das Paradoxon von Neels Gemälden, als mit einer Spannung aufgeladen, die mitunter als Erotik bezeichnet wird, während die Arbeiten selbst das Erotische zu verweigern scheinen. Weiterhin spricht Molesworth von der Nacktheit in Neels Akten, und meint damit das Unvermittelte darin. Wenn man ihre Gemälde betrachtet, kann man sich vorstellen, dass Neel ihre Modelle durchdringend beobachtet, denn diese schauen herausfordernd aus den Bildern zurück. Das Modell ist auf Augenhöhe mit der Perspektive der Betrachtenden. Neel sondiert beherzt, ohne Anbiederung und voller Wahrhaftigkeit ihrem Gegenüber.

Auch ihre Gemälde, in denen sie (heterosexuelle) Beziehungen abbildet oder aus welchen Neels Begehren ablesbar scheint, zeichnet eine Befreiung von Erwartungen an Geschlechterrollen aus. Pregnant Julie and Algis, 1967, ist das Doppelporträt einer nackten schwangeren Frau und eines bekleideten Mannes, der hinter ihr liegt. Die Polarität zwischen der bekleideten und der nackten Person wirkt jedoch nicht wie ein Ausdruck einer Machtdifferenz. Die Nacktheit der Schwangeren erscheint herausfordernd, als würde das Modell, oder Neel, sich weigern, romantischen Idealen von Mütterlichkeit zu entsprechen. Einen ähnlichen Ausdruck kann man in ihren zahlreichen Gemälden von Schwangeren finden, daneben Blicke von Unsicherheit – ebenfalls eine Emotion, welche in Darstellungen von Schwangeren ausgelassen wird.

Die Personen in Neels Bildern benötigen niemand anderen zur Definition ihrer selbst; sie zeigt deren Sexualität und Körperlichkeit als selbstverständlichen Aspekt eines Menschen, ungeachtet, ob es sich dabei um ein Kind oder eine erwachsene Person handelt, unabhängig von Geschlecht und Alter. Hierzu gehört auch die Darstellung verschiedenster Zustände und Lebensphasen des Seins, wie ihre Gemälde, die das Wochenbett darstellen, oder das Porträt Andy Warhols mit den auf seinem Brustkorb sichtbaren Narben des 1968 auf ihn verübten Attentats. Neel stellt eine Bandbreite weiblicher Erfahrungswelten dar; sowohl wie Frauen sich außerhalb eines männlich geprägten Bezugsrahmens erfahren, als auch ihre Reaktion auf diesen. Denise Bauer beschreibt diese Sensibilität wie folgt: „It is Neel's skill at capturing and deconstructing this complex blend of what women are ‘supposed to’ experience and how they may actually experience the male gaze that expertly cuts to the reality of so many women's experiences of themselves and their bodies.“

Es gibt einige Filmaufnahmen von Interviews mit Neel, nachdem sie mit über siebzig Jahren durch eine Retrospektive im Whitney Museum zu Anerkennung kam, und man plötzlich von der alten Künstlerin hören wollte, deren Werk institutionell legitimiert worden war. Sie ist darin als aufgeweckte und freche Frau zu erleben, die sich über Ihren Erfolg freut – die aber auch fünfzig Jahre ohne Sichtbarkeit in der breiten Öffentlichkeit, geradlinig ein großes Werk geschaffen hatte. Im Alter von 80 Jahren porträtiert sich Neel selbst: nackt, mit einem Pinsel und Mallappen in der Hand, auf einem Sessel sitzend, der auch auf anderen Gemälden zu sehen ist. (Alice Neel Self-Portrait | National Portrait Gallery) Neel zeigt sich alleine, autonom, selbstbewusst. Die Haltung im Dreiviertel-Profil unterscheidet sich von der meist frontalen Perspektive auf ihre Modelle. Dies erklärt sich aus der Realisierung heraus: Ihr Blick musste zwischen Spiegel und Leinwand hin und her wandern; um sich möglichst wenig zu bewegen, dreht sie vor allem ihren Kopf. Sie stellt sich damit in die Traditionslinie von Künstler*innen, die sich bei Ihrer Tätigkeit zeigen und dadurch bildnerisch ihren Selbstausdruck und ihr Handlungsvermögen unterstreichen. Die Bildgebung erinnert an das Akt-Selbstporträt Lucian Freuds Painter Working, Reflection, 1993. Beide sind malende Künstler*innen, die sich selbst so offenlegen, wie sie es mit ihren Modellen tun: Sie zeigen sich nackt in ihren Ateliers, beim Malen. Freud trägt nur Arbeitsschuhe ohne Schnürsenkel, eine Palette in einer und einen Malspachtel in der anderen Hand. Er geht mit seinem Abbild so ungeschönt um, wie man es aus seinem Werk kennt, und stellt seinen aufrechten, doch vom Alter gezeichneten Körper dar.

Lucian Freud (1922-2011) schuf im Laufe seines Lebens zahlreiche Selbstporträts, doch neben Painter Working, Reflection gibt ein zweites Gemälde, welches ihn im hohen Alter bei seiner künstlerischen Tätigkeit zeigt, und welches ich deshalb zum Vergleich mit Alice Neels Selbstporträt heranziehen möchte. Die Arbeit The Painter Surprised by a Naked Admirer, 2004-2005, ist ebenfalls ein Statement zu seinem Werk – meiner Meinung nach, malerisch aber eine seiner schwächsten Arbeiten. Das Gemälde zeigt Freud in seinem Atelier, das Bild, das wir sehen malend. Während er sich bekleidet abbildet, sitzt zu seinen Füßen ein junges nacktes, weibliches Modell. Die Gegenüberstellungen von bekleidet/nackt, aufrecht/kauernd, passiv bettelnd/aktiv malend bilden eine Geschlechter-Dichotomie ab, wie sie unzählige Male gezeigt wurde, und die Frau zum Objekt des Blickes macht. Interessanterweise ist diese Vergeschlechtlichung des Aktes etwas, das in seinen sonstigen (Akt-)Porträts, die mit einem unerbittlichen, aber hingebungsvollen Realismus ausgeführt sind, nicht stattfindet. Dass Freuds weibliche Modelle oftmals Geliebte waren oder im Laufe des Malprozesses dazu wurden – zudem einige von ihnen die Mütter seiner Kinder sind – ist bekannt. Mit der gleichen intimen Intensität malt er aber auch Männer, wie zum Beispiel seinen Assistenten David Dawson oder Leigh Bowery.

In seiner zweiten Lebenshälfte gewann Freuds Werk an künstlerischer Ausdruckskraft und Anerkennung. Deshalb ist verwunderlich, dass Freud, der psychologische oder symbolistische Deutungen seiner Arbeiten ablehnte, mit zweiundachtzig Jahren ein solches Bild inszenierte, und darauf bestand, es prominent in der National Portrait Gallery zu präsentieren. Die Presse nannte den Titel „humorvoll“. Im Guardian wird ein mit Freud befreundeter Autor zitiert, der die junge Frau im Bild als „Muse oder Nervensäge, vielleicht beides“ beschreibt, und deren Pose, in der sie sich scheinbar bettelnd an Freuds Bein klammert, als „sehr berührend […], man erfährt sehr deutlich ein Gefühl für die Beziehung“. Weiterhin klingt die Interpretation des kauernden Modells als Personifikation der Malerei an, die den Altmeister anbettelt — somit wird die Frau, ganz nach kunsthistorischer Tradition, ihrer Identität beraubt und fungiert als Allegorie. Freud perpetuiert in diesem Gemälde sein Image als anziehender Künstler, für den jede*r, insbesondere aber jede Frau, Modell stehen möchte. Seine Geste, sich mit einem Modell zu seinen Füßen abzubilden, ist die Machtgeste des heterosexuellen, männlichen Künstlers, und so kaum von einer Künstlerin gemalt denkbar.

Weit über die Selbstinszenierung von Künstlerinnen* hinaus, ist der Einsatz des eigenen Körpers und des eigenen Bildes ein wirkungsvolles Mittel, die eigene Handlungsfähigkeit zu konstituieren. Dies ist vor allem von Bedeutung, um die Deutungsmacht über Bilder – darüber, wer auf welche Art repräsentiert wird – zu korrigieren und somit für feministische Künstlerinnen* eine wirkungsvolle Strategie.

Suzy Lake (*1947) setzt sich seit den frühen 1970er Jahren anhand ihres eigenen Bildes performativ-fotografisch mit Frauenbildern und Weiblichkeit als Maskerade auseinander. Anders als Cindy Sherman, auf deren Werk eine frühe Begegnung mit Lake Einfluss hatte, nutzt sie Selbstinszenierung nicht, um verschiedene weibliche Charaktere darzustellen, sondern um darzulegen, wie insbesondere Frauen mit gesellschaftlichen Erwartungen an die Art ihrer Selbstpräsentation, konfrontiert werden. „I knew what I should look like […] I was told that all my life“, zitiert Sara Angel Lake. Was mit der Beschäftigung mit Zeitschriftenbildern, kulturellen Prägungen und modischen Vorstellungen begann, mündete in die Auseinandersetzung mit den paarweise auftretenden Stereotypen über das Alter in der westlichen Welt—ein Mann reift, wenn er altert; eine Frau verwelkt – als ein politischer Akt.

In Medienbildern, die vor allem bei Frauen* jugendliche Schönheit bevorzugen, fällt die alternde Frau* zunehmend durch das Raster. Wie um dem im Alter fortschreitenden Verschwinden von Frauen als Protagonistinnen entgegenzuwirken, schuf Lake Arbeiten, die ihre Präsenz zum Thema machen. In der Arbeit Extended Breathing Under Porch Light, 2009–2010, nimmt Lake sich selbst mit Langzeitbelichtung innerhalb eines häuslichen Gartens auf. Sie muss stillstehen, damit ihr Bild nicht verwischt, um nicht zu verschwinden. „[She] is insisting on a presence inside the frame […] I think it’s about a much broader question of how women insert themselves inside of a social and political space“. Nicht nur die Unsichtbarkeit als Frau eines gewissen Alters ist eine mögliche Lesart, sondern auch die Ambivalenz zwischen der weißen, scheinbar privilegierten Frau, vielleicht einer Hausfrau, die in einem umzäunten Einfamilienhaus mit Garten lebt, jedoch gesellschaftlich vor allem als Konsumentin relevant ist. Eine weitere Deklination des Themas findet sich in der Serie Reduced Performing, 2008-09, für die Lake sich in verschiedenen Outfits auf einen Flachbettscanner legte und minimale Aktionen vollführte: atmen, blinzeln und weinen. Ihre Kleidung ist von einer uneitlen Normalität gekennzeichnet; es könnte Lakes Alltagskleidung sein. Wo sich ihr Körper beim Scan-Vorgang bewegt, kommt es zu Unschärfen bzw. Glitches.

Die Arbeit Performing Haute Couture, 2014, ist inhaltlich das Gegenstück. Lake zeigt sich gut ausgeleuchtet in stolzer Pose einen Commes-des-Garçons-Zweiteiler tragend. Hier schlüpft sie in eine Rolle, in der ältere erfolgreiche Frauen* gern gezeigt werden: Die der Grande Dame. Das Styling lässt an die Performance-Künstlerin Marina Abramovic oder Anna Wintour, Chefredakteurin der US-Vogue, denken; an Frauen aus der Schnittmenge „Society“ und Kultur. Laut Georgiana Uhlyarik ist das geschaffene Bild ein Statement, um Kommerz, Mode, Wünsche, Ambitionen, Wirkungsmacht zu veranschaulichen und zu verkörpern. Hier ist eine Ambivalenz spürbar: einerseits zeigt sich Lake erfolgreich, selbstermächtigt und selbstbestimmt – sie präsentiert Suzy Lake, ihre Schöpfung –, gleichzeitig macht sie, wie immer in ihren Arbeiten, die Konstruktion dieser Identität bereits im Titel der Arbeit deutlich.

Das Frühwerk der Malerin Joan Semmel (*1932) war geprägt von der starken Ausstrahlung der sogenannten New York School. Nach einem mehrjährigen Aufenthalt in Spanien kehrte sie 1970 nach New York zurück und sah sich ständig mit sexualisierten Medienbildern im Stadtbild konfrontiert. Unter diesem Einfluss begann Semmel ihre ersten sex pictures zu malen. Aus schnellen expressiven Zeichnungen nach der Vorstellung und nach Modellen entstanden gestische Gemälde. Um einen genaueren Blick darzustellen, arbeitete sie schließlich nach selbst gemachten Fotovorlagen von intimen Paaren, brach aber den Realismus der Figuren durch deren Farbgebungen.

“I was never figural. What I was looking for were images that were iconic. I was looking for ways of making images that women would see as sexual for them, and so I wanted those images to register, and that is part of why I left the abstraction behind — because the abstract images are more diffuse.”

Sexualität wird bei Semmel nicht kritisch oder ironisch behandelt, wie es zum Beispiel die Bildhauerin Lynda Benglis in ihrer Anzeige in Artforum (1974) tat, indem sie mit einem überdimensionierten Dildo posierte; oder esoterisch, wie manche von Judy Chicagos bildhaften Werken scheinen, sondern es ist ernsthafte Auseinandersetzung mit dem Thema. Daran gekoppelt ist die Abbildung einer Gleichberechtigung zwischen den heterosexuellen Paaren, die sie abbildet, und die im Kontrast zur Repräsentation von Sexualität stand, die während der pornographischen Welle der 1970er Jahren zu sehen war. Joan Semmel ist nah an ihrem Modell – unabhängig davon, ob sie es selbst ist, oder eine andere Person – und vermittelt damit eine Wahrhaftigkeit, die ungeschminkt, aber sinnlich ist.

“Pornography is fashionable now; it is considered fine, just another entertainment. But the attitudes that are expressed in most pornography are abhorrent. My sexual paintings might be very disturbing to these same people who watch pornography, because the dehumanizing aspect is no longer there. So it makes them nervous.”

Die Führung des Blickes in ihren Bildern ist bemerkenswert. Obwohl Semmel die Körper oftmals so anschneidet, dass die Köpfe außerhalb des Formats liegen, was als entmenschlichend oder objektivierend wahrgenommen werden kann, bewirkt die extreme Perspektive in vielen ihrer Bilder, dass der*die Betrachter*in auf diese fragmentierte Körper blickt, als würde man an seinem eigenen Körper herabschauen.

Als inhaltliche Konsequenz setzte Semmel sich selbst – alleine oder auch gemeinsam mit einem Partner – in ihre Gemälde ein. Das Gemälde Intimacy/Autonomy, 1974, zeigt Semmel und einen Mann von den Schlüsselbeinen abwärts. Sie liegen mit angezogenen Beinen nahe beieinander, berühren sich im Bildfeld aber nicht. In ihren Selbstporträts macht Semmel ihren Blickwinkel zunächst durch subjektive Anschnitte zur Ich-Perspektive der Betrachtenden, wie bei On the Grass, 1978. Später schafft sie dies, indem sie Spiegelungen in die Kompositionen einbezieht, wie Body and Sole, 2004. Beide Gemälde zeigen ähnliche Partien ihres Körper: angewinkelte Beine, den Bauch, der sich durch die Haltungen faltet, Brüste. Auf dem zweiten Bild ist jedoch einer ihrer Füße gedoppelt, da ein Großteil des Gemäldes von einem Spiegelbild eingenommen wird. Daraus schaut Semmel – mit der Kamera auf sich selbst gerichtet – auf uns als Betrachtende zurück. Semmel bezeichnet diese Umkehrung des Blicks als eine Destabilisierung der Sehenden und Gesehenen.

In den 1980er und 90er Jahren setzte sich Semmel innerhalb von Serien mit dem sozialen und medialen Blick auf Frauenkörpern auseinander, sowie mit dem wertenden male gaze, den Frauen internalisiert haben. Ihre Motive sind Selbstporträts in Fitnessstudio-Umkleiden, Schaufensterpuppen oder Körper am Strand. Schließlich wendete sie sich in den letzten zwanzig Jahren wieder Akt-Selbstporträts zu, die sie alleine zeigen, aber in denen sie sich oftmals vervielfältigt. In transluzenten Schichten gemalt, ähneln manche Werke den Bewegungsstudien Eadweard Muybridges (z. B. Triple Play, 2011). Andere haben eine geisterhafte Anmutung (Disappearing, 2006), die auf die Fragilität des Lebens, die im Alter zusehends präsenter wird, hinzuweisen scheint. Diese Arbeiten zeigen sie bezeichnenderweise als ganze Figur, so als würde sie diese Gedanken in sich verkörpert betrachten wollen, und als benötigte sie dazu eine gewisse Distanz. In ihren letzten Arbeiten – mit inzwischen weit über achtzig Jahren – kehrte Semmel zu der Abbildung einer subjektiven Perspektive auf den eigenen Körper zurück. Dass sie immer noch eine schöne Frau ist, mindert nicht die Bedeutung, Akte einer alten Frau zu sehen, die sich selbstbewusst in ihrer Körperlichkeit zeigt, ohne Anerkennung zu bedürfen oder gefallen zu müssen.

Ich begann diesen gedanklichen Ausflug zu Werken und Selbstdarstellungen älterer Künstlerinnen*, um dort nach alternativen Bildern vom Frau*sein zu suchen. Wenn wir unsere Blicke vom straffen jungen Körper hin zu einer Subjektivität wenden, finden wir dort zu einer erweiterten Darstellung von Körperlichkeit? Präsenz und Sexualität sind hierbei gleichberechtigte Sujets, die einander bedingen. Die Autorin und Aktivistin Audre Lorde wünschte sich ein Feiern des Erotischen in jeder Situation. Das Erotische meinte sie nicht nur sexuell, sondern als eine Lebenskraft: „In touch with the erotic, I become less willing to accept powerlessness, or those other supplied states of being which are not native to me, such as resignation, despair, self-effacement, depression, self-denial.“ Lorde schreibt, wie sie als Schwarze lesbische Frau diese erotische Energie (erotic charge) direkt erfahren hat, jedoch Frauen, die in einer europäisch-amerikanischen, patriarchalen Tradition agieren, diese nicht ohne weiteres erleben können. Für Lorde ist die Besinnung auf das Erotische als zutiefst schöpferische Quelle, angesichts einer rassistischen, patriarchalischen und anti-erotischen Gesellschaft, eine weibliche und selbstbehauptende Handlung.

Die Unsichtbarkeit von älteren Frauen und ihrer Sexualität begründet sich in der kulturellen Verknüpfung von Schönheit mit Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit. Einerseits wird die Sexualität kulturell im weiblichen Körper verankert, doch scheint dies andererseits nur so lange zu gelten, wie die Frau jung und gebärfähig ist, oder ihre körperliche Jugendlichkeit erhalten konnte. Obwohl älteren Frauen Sexualität „zugestanden“ wird, so ist die Darstellung davon – auch die sexuelle Selbstdarstellung im Werk von älteren Künstlerinnen – selten. Wenn wir von Körpern als diskursive und nicht als essentielle, biologische Einheiten ausgehen, so ist das Motiv des Begehrens textuell und performativ in Körperlichkeit eingeschrieben. Neel, Lake und Semmel widersetzen sich der Erwartung, dass Frauen* sich jenseits eines gewissen Alters vornehm zurückziehen. Indem sie ihren Körper, also ihr Abbild in ihrer Kunst einsetzen, manifestieren sie ihr Handlungsvermögen.

References

Bauer, Denise. “Alice Neel's Female Nudes.” Woman's Art Journal 15, no. 2 (1994): 21-26. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://doi.org/10.2307/1358600.

Beckenstein, Joyce. “Joan Semmel: Naked Came The Nude.” Woman's Art Journal 36, No. 2 (2015): 3-11. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26430651.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books, 1972; London: Penguin Classics, 2008.

Higgins, Charlotte. “Painting of an image of a painting being painted: The latest self-portrait by Lucian Freud goes on display.” The Guardian, Wed 13 Apr 2005. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/apr/13/arts.artsnews2.

Lorde, Audre. “The Uses of the Erotic. The Erotic as Power.” In Sister Outsider. Berkeley: The Crossing Press, 1984. 53-59.

Mapplethorpe, Robert: Louise Bourgeois,1982/1991, in Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/robert-louise-bourgeois-ar00215.

Molesworth, Helen und Neel, Ginny. Alice Neel: Freedom. New York: David Zwirner, 2019.

Neel, Alice: Self-Portrait, National Portrait Gallery. https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.85.19.

Samet, Jennifer. “Beer with a Painter: Joan Semmel,” Hyperallergic, August 25, 2018. https://hyperallergic.com/457281/beer-with-a-painter-joan-semmel/.

Semmel, Joan auf Alexander Gray Associates. https://www.alexandergray.com/series-projects/joan-semmel8?view=slider#1 .

Silas, Susan. “On Sexual Paintings and Shifting Images: An Interview with Joan Semmel.” Hyperallergic, May 6, 2015. https://hyperallergic.com/198526/on-sexual-paintings-and-shifting-images-an-interview-with-joan-semmel/.

Uhlyarik, Georgiana (Hgin.). Introducing Suzy Lake. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2015.

Vares, Tiina. “Reading the ‘Sexy Oldie’: Gender, Age(Ing) and Embodiment.” Sexualities 12, no. 4 (2009): 503-524. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460709105716.